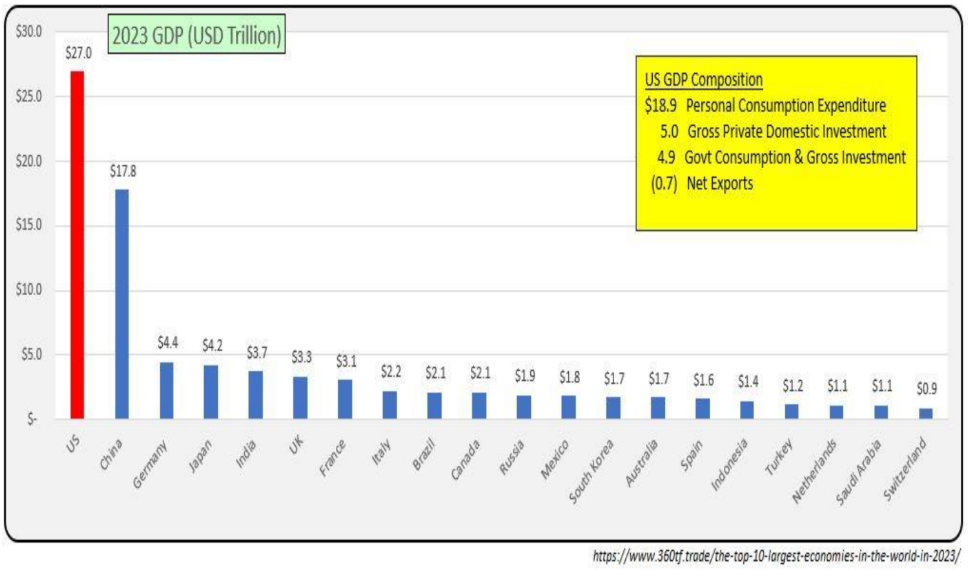

GDP represents the total income of a country in one year. The U.S. has the largest GDP, followed by China, with Germany, Japan, India, and the UK trailing at a distant position.

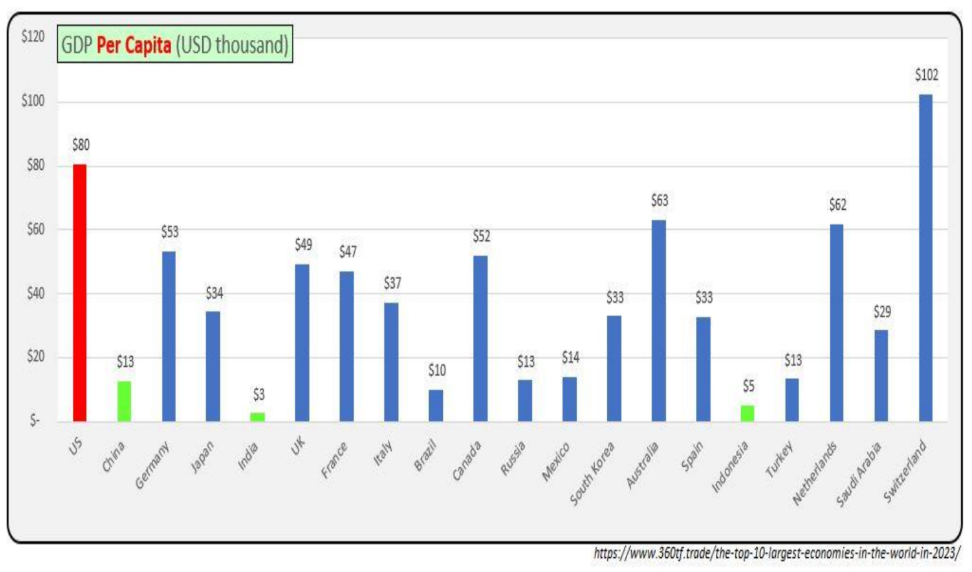

A country’s GDP is closely linked to its population. While China has a large GDP, it took 1.2 billion people to achieve it. On a per capita basis, China’s GDP is relatively low.

China’s economy is primarily driven by its role as the world’s largest manufacturer, exporting goods worldwide. GDP also comes from infrastructure investments (such as roads, high-speed rail, and canals) and property investment, which accounts for 25% of its economy.

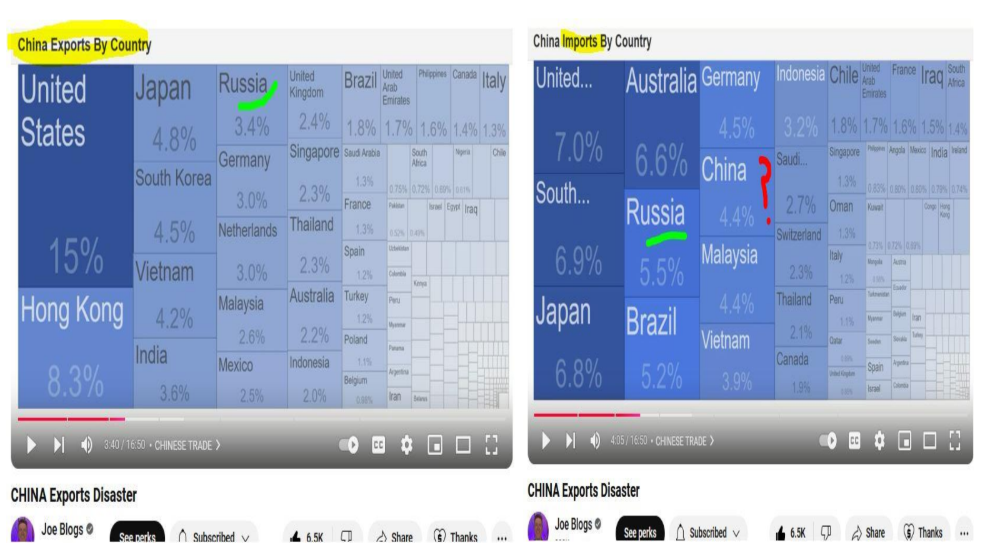

China’s manufacturing income relies heavily on imports and exports. A significant portion of its exports go to the U.S. and Hong Kong. Hong Kong, in turn, operates as an export-driven economy, processing Chinese imports and re-exporting them to other countries.

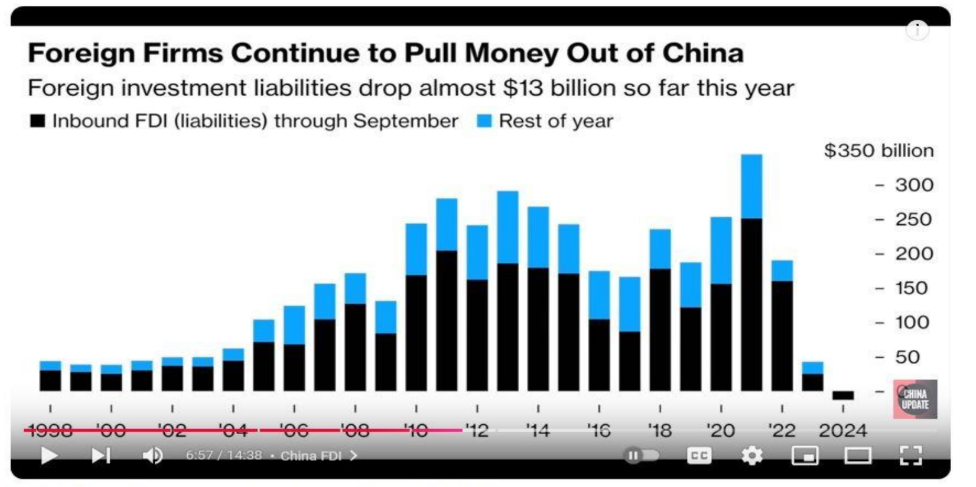

Where does the money come from to fund these investments? Is it derived from net earnings or debt? A substantial portion has historically come from foreign investment, but this has slowed significantly over the past three years.

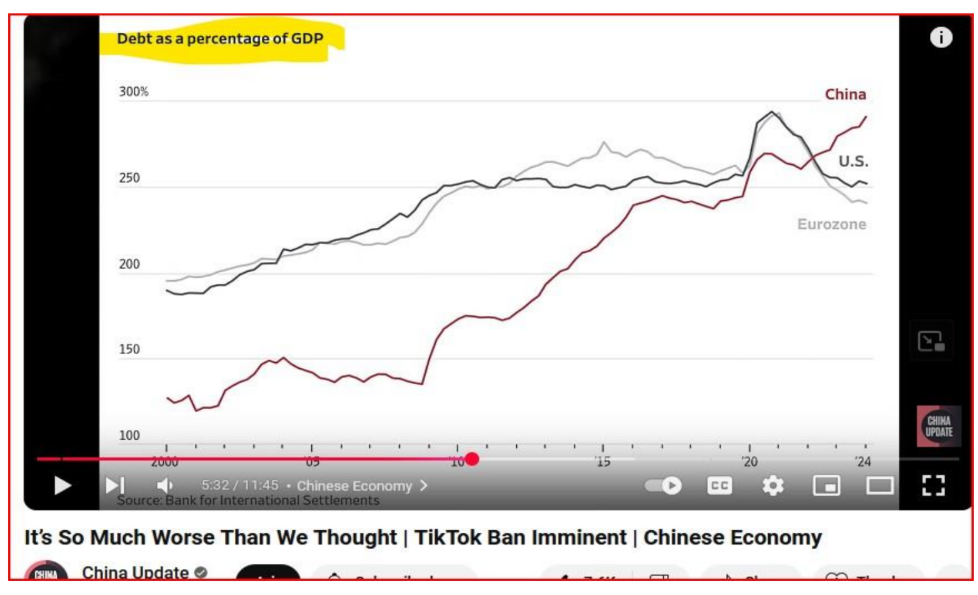

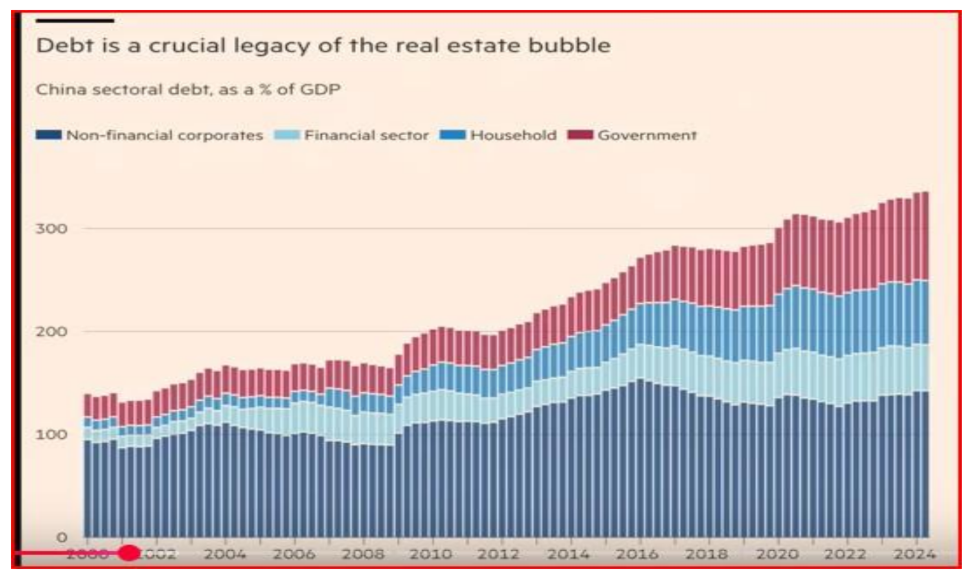

In addition to foreign capital, China has fueled its growth through debt, which now stands at three times its GDP. However, GDP represents gross income—it does not reflect net income or a country’s net asset value.

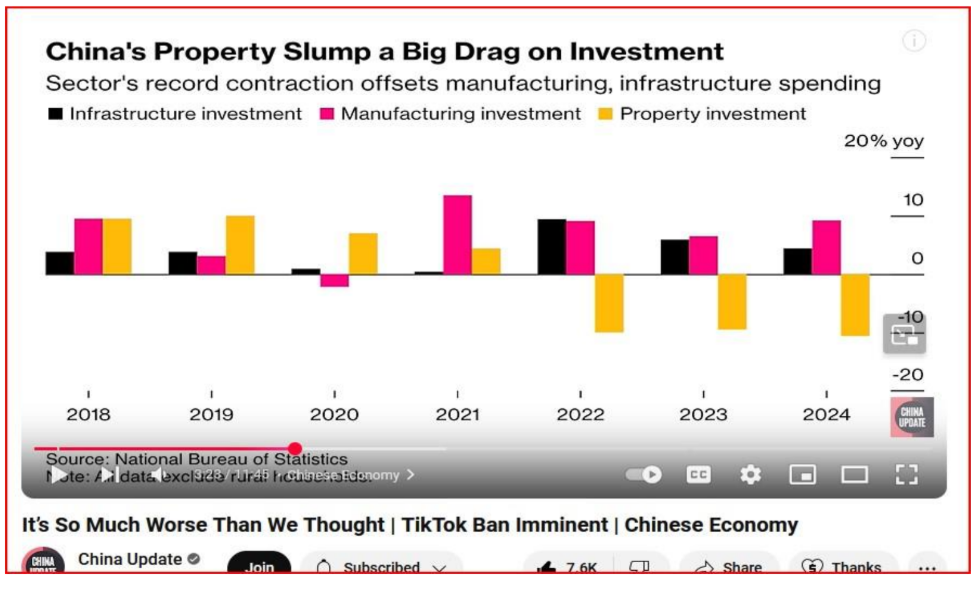

Among China’s three primary economic drivers—manufacturing, infrastructure, and property— which sector is incurring the most debt? Does that sector generate enough income to service it? Infrastructure, for example, does not necessarily produce net operating income (NOI).

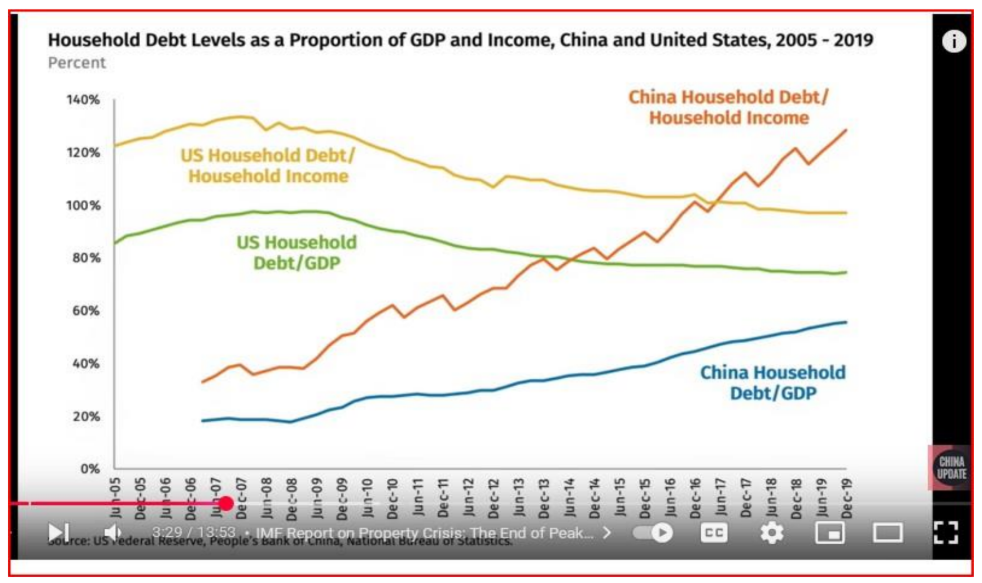

China’s property market primarily consists of condominiums and houses, making it a major source of household debt. GDP reflects gross income, while household income represents net earnings. A steady rise in household debt relative to income raises concerns about whether income levels are sufficient to service that debt.

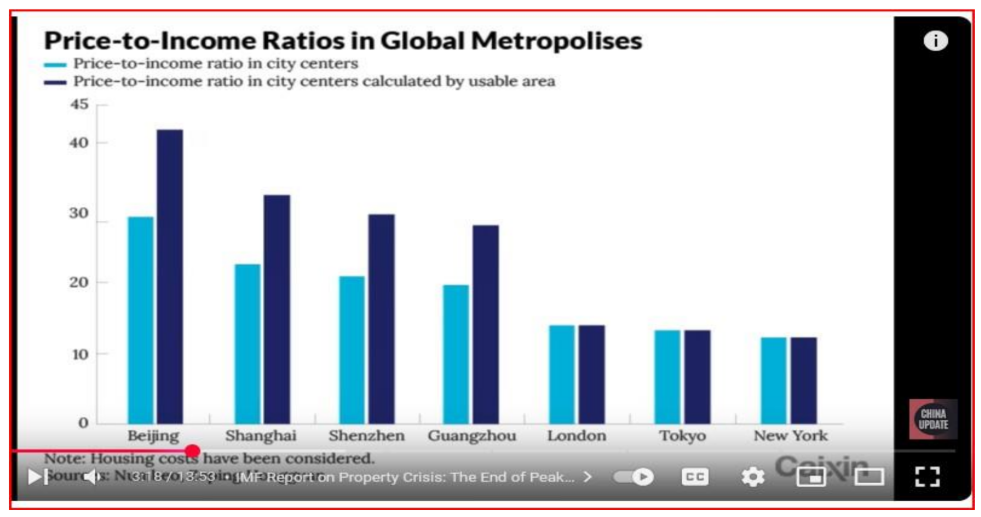

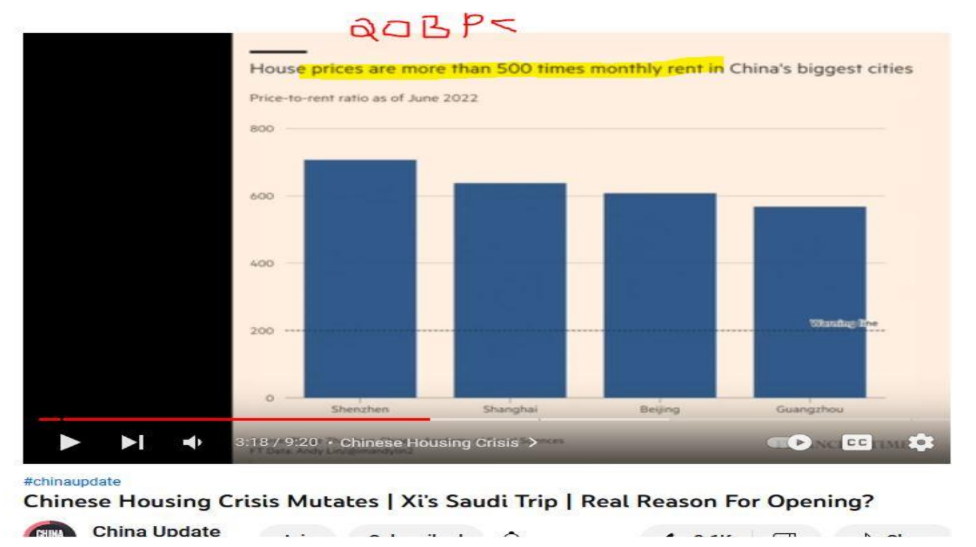

Property values in China have soared far beyond affordability. While cities like London, Tokyo, and New York have property price-to-income ratios of around 10, China’s ratio is between 25 and 30, making homeownership unattainable for many.

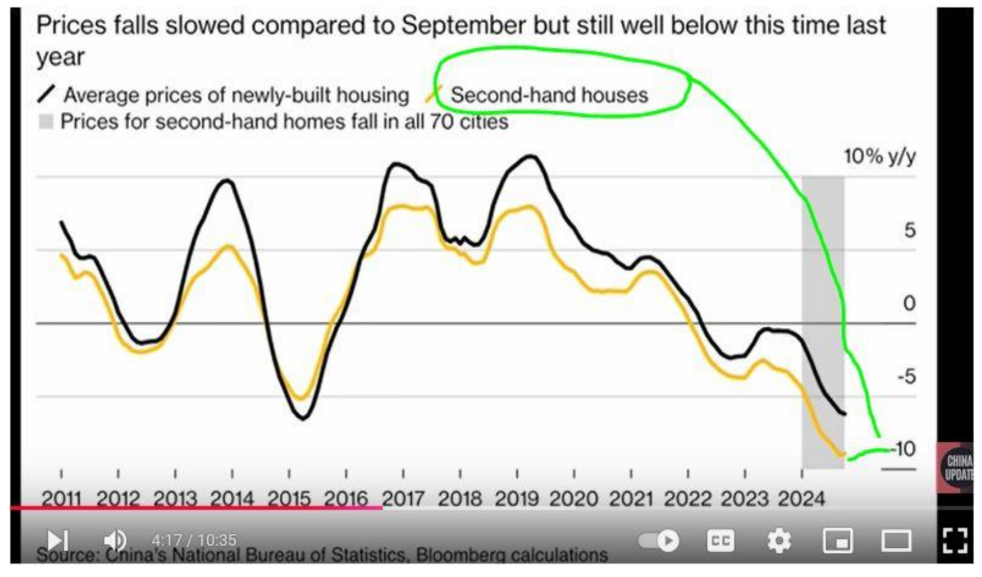

For years, real estate investment was considered a pathway to financial success. Many people acquired second properties not for rental income but in anticipation of continuous price appreciation. However, with home values now declining, that forward momentum has ended.

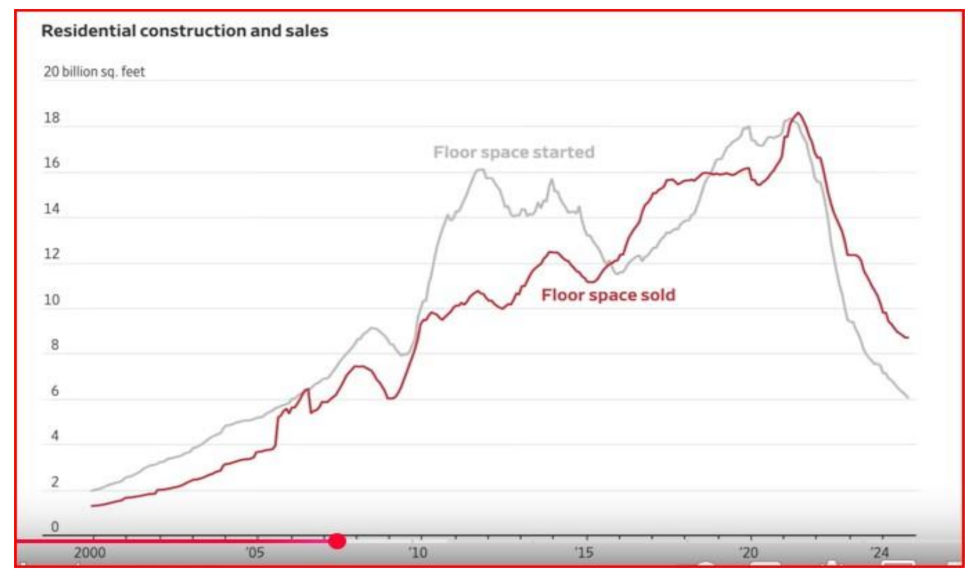

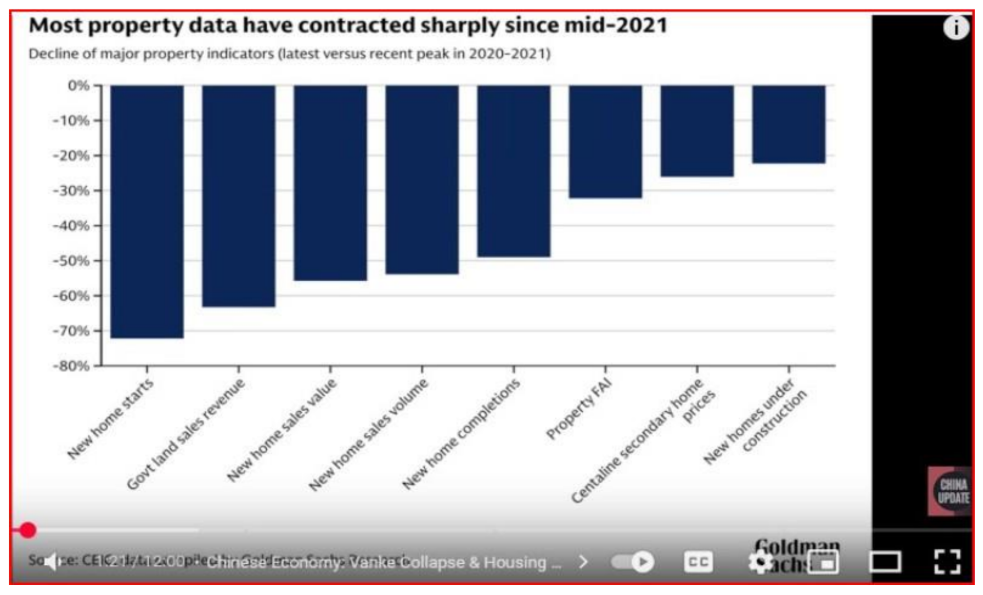

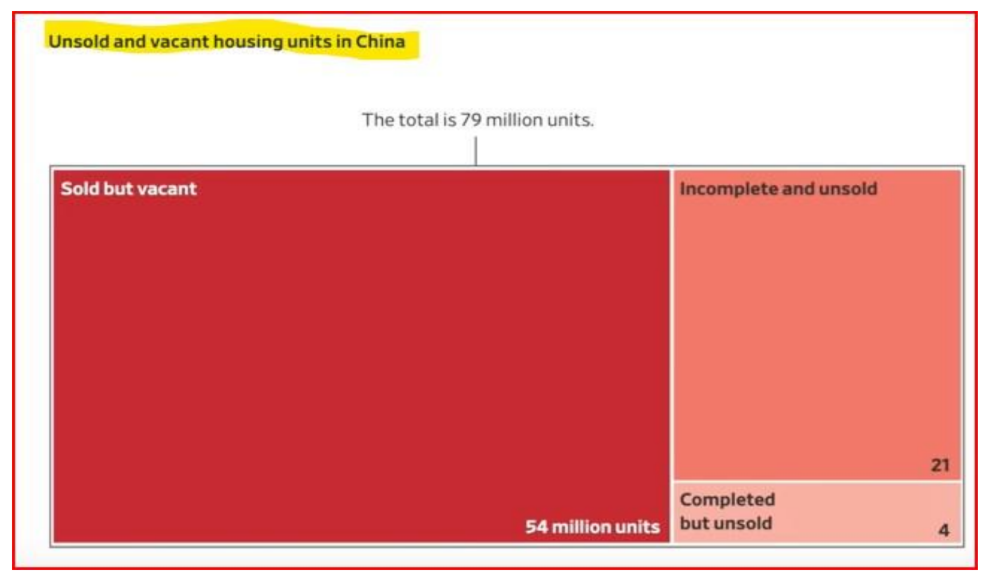

As prices soften, demand for additional properties has plummeted, leading to a sharp decline in construction. This downturn threatens contractors’ ability to finance projects and repay foreign debt.

With 25% of China’s GDP tied to real estate, the sector’s collapse has far-reaching consequences. Reduced construction has not only hurt employment but has also led to a sharp decline in local government revenue from land sales, affecting their ability to service debt.

Many individual investors who purchased second properties are now at risk. Most of these properties were not rented out, with rental yields estimated at around 0.2%. Instead, they were held for speculative capital gains, which are now uncertain. While some properties were funded through family support and remain debt-free, those financed with loans face significant challenges.

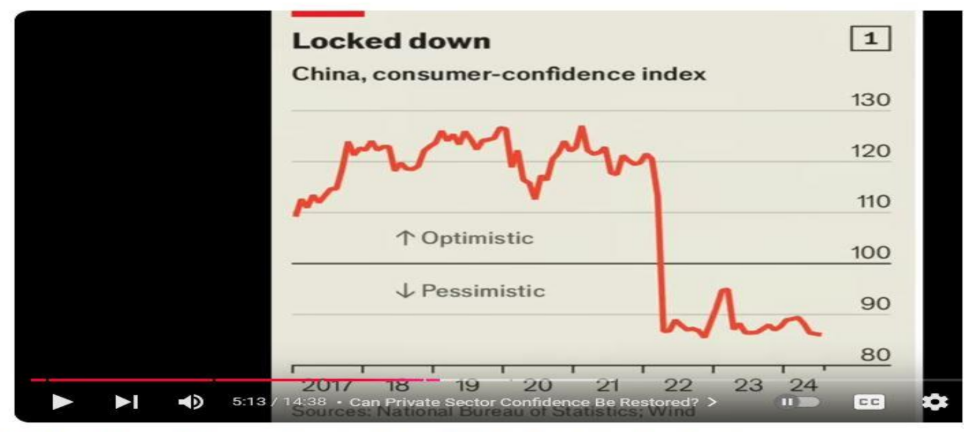

Incomplete and unsold properties are adding to an oversupply, further depressing the market. This downturn is directly impacting consumer confidence. As confidence weakens, domestic consumption declines, placing more pressure on exports to sustain economic growth.

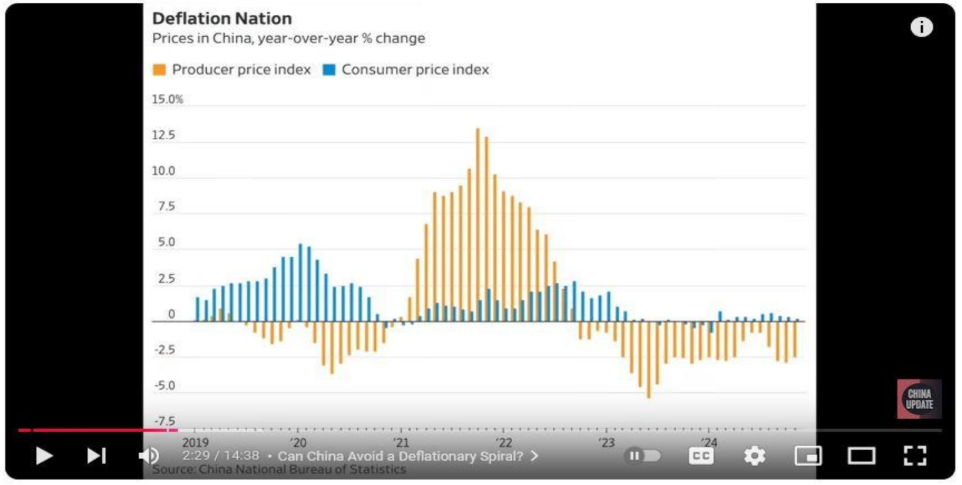

With falling property values, rising unemployment, and lower consumer spending, China is entering a period of deflation—similar to what the U.S. experienced in the 1930s and Japan during its “Lost Decade.”

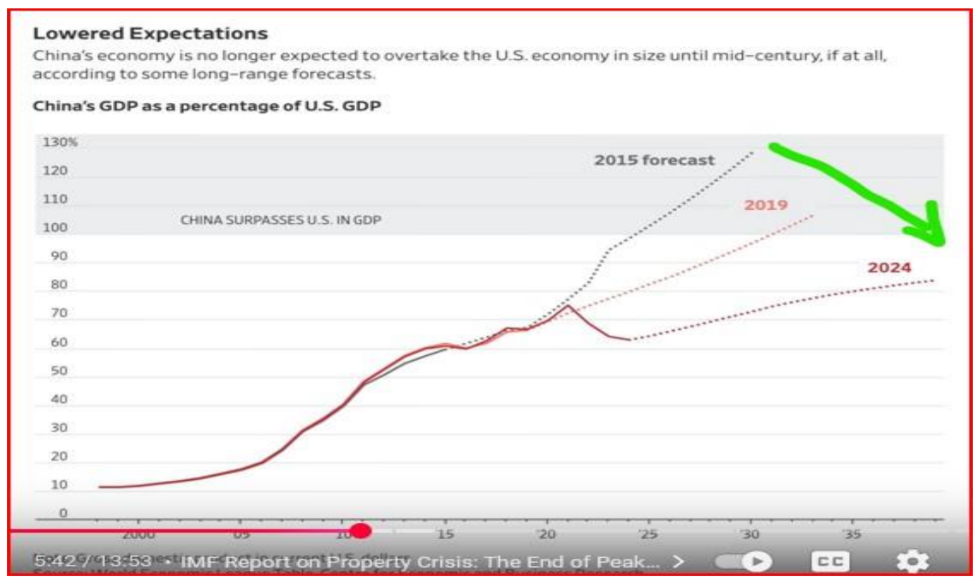

China also faces additional headwinds, including high government debt limiting infrastructure spending and global tariffs impacting manufacturing. These factors make future economic growth less optimistic.

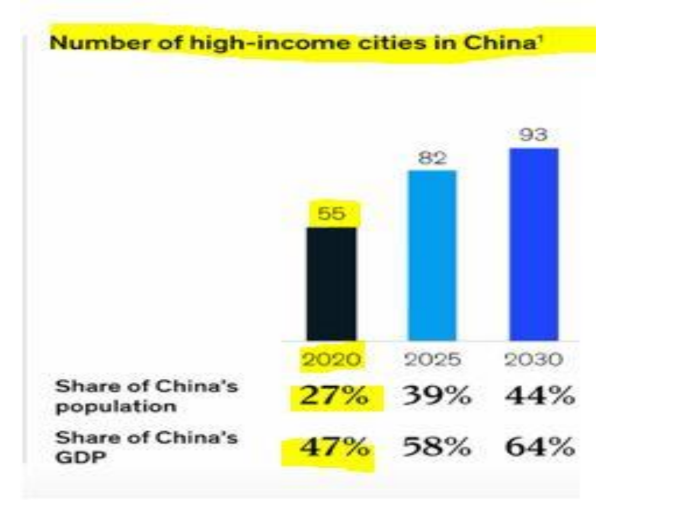

A significant economic divide exists between China’s urban and rural populations. Nearly half of China’s population lives in rural areas, where annual per capita income is just $750. The urban property crisis is particularly concerning because urban dwellers drive domestic demand. Slower economic growth could hinder migration from rural to urban areas, potentially increasing social instability.

China’s economic challenges—falling property prices, high debt levels, and weakening consumer confidence—are converging to create a complex and uncertain future. How the government navigates these issues will determine whether China can stabilize its economy or faces prolonged economic stagnation.

Bill Knudson, Research Analyst LANDCO NEXA